Nature Versus Plastic: A View From The Science Lab

Find out how nature organisms are adapting to the introduction of microplastics entering the food chain, and if we, humans, will pay the price.

— Mr. McGuire to Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman) in the 1967 film The Graduate.

In their 100-odd-year history, plastics have evolved from their humble roots as an explosive substitute for ivory billiard balls and inexpensive material for cheap and cheerful costume jewelry to an integral part of our daily life. We can even print plastic parts at home, thanks to consumer-grade 3D printers.

But there is a dark side to all this.

Plastic waste is proliferating, threatening the food chain and our human health. And it’s not limited to the plastic bottles littered on the side of the highway; plastics are also quietly disintegrating in places you might not expect, such as synthetic fabrics in your washing machine, producing microplastic particles that enter undetected into the waste stream.

The US is a top contributor to plastic waste, and single-use plastics (including wipes, plates, cups, tableware, packaging, and diapers) are a major source of plastics pollution. Unfortunately, during the pandemic, plastic waste increased dramatically (by as much as 8 million tons according to some estimates) as consumers, fearing Covid transmission, avoided sharing reusable items.

The problem is international in scope, with poorer countries often the recipient of plastics pollution discarded by richer nations. The United Nations is considering a new, legally binding treaty by 2024 to address the problem of plastics pollution globally.

And here in the US, the EPA published its own national recycling strategy in November 2021, calling for recycling 50% of municipal solid waste by 2030, funding in part by the infrastructure bill that included $350 million in grants for solid waste treatment and recycling.

But is placing the focus squarely on recycling plastics the right strategy? Probably not. Instead, laboratory researchers are calling for a more holistic approach that addresses the full circular lifecycle of plastics, including making plastics that degrade quickly on their own without the need for intervention.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, A Symbol Of Failed Efforts To Control Plastics Pollution

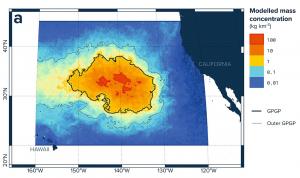

The poster child for plastics pollution is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (see on the right).

Prevailing winds and ocean currents create spinning gyres that trap floating plastics in continent-sized fields that can be seen from space.

Environmentalists, such as the young Dutch inventor Boyan Slat, founder of The Ocean Cleanup, have created innovative new technologies to pick up trash in the ocean, as well as rivers and harbors.

But plastic pollution just keeps coming. Plastics are impacting the most remote areas of the world.

There’s More Plastic In The Atmosphere And Under The Ocean’s Surface Than Meets The Eye

Out of sight, out of mind.

It’s easy to ignore the growing threat of microplastics pollution.

But it’s a real and growing problem.

For example, Roadways are a major source of microplastics, which then spread in the atmosphere. According to researcher Dr. Natalie M. Mahowald, vehicle tires shed small particles of rubber that can become airborne, traveling aloft for nearly a week.

Washing synthetic fabrics in a washing machine is another major source of microplastics pollution. This can be mitigated to a great extent by fitting specialty filters to prevent small plastic debris from entering the waste stream.

Industrial plastic pellets, called “nurdles,” are another chief source of microplastic pollution. These are shipped around the world to factories, where they are processed into plastic parts. Accidents at sea where containers full of nurdle pellets get dumped into the sea are as damaging to the environment as major oil spills.

New research techniques are making it easier to track the extent of microplastics pollution across the world’s waterways. Madeline Evans and Professor Christopher Ruf from the University of Michigan were recently recognized for their new method of interpreting “roughness” on the surface of water, enabling satellite-based radars to identify the presence of microplastic pollution.

But what happens under the surface of the water?

Here researchers are making some very disturbing discoveries.

It’s literally “raining” microplastics within the ocean depths

As microplastics disintegrate, they lose buoyancy and drift down to the ocean floor like rain.

Microplastics Are Threatening Plant And Animal Life, Including Humans. Can Ecosystems Adapt In Time Before It’s Too Late?

What is the impact of microplastic pollution on the environment?

Thanks to natural selection, ecosystems are responding. Scientists have identified new traits arising among some insects, allowing them to eat plastics.

Mealworms are also able to adapt to eating plastics as a food source, including potentially toxic additives found in polystyrene.

Other species are adapting to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, forming “neopelagic communities” living on plastic trash floating on the surface of the water.

Read more...

Julia Solodovnikova

Formaspace

+1 800-251-1505

email us here

Visit us on social media:

Facebook

Twitter

LinkedIn

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.