Political Power, Personal Portfolios, and Risks for Corporate Governance

In the US, the debate over whether members of Congress should be allowed to trade individual stocks has moved from the ethics pages to the front page. Media reports have highlighted trades made after closed-door Covid briefings, systematic investing in industries overseen by lawmakers’ own committees, and repeated violations of the STOCK Act’s already modest disclosure requirements. Proposals to ban individual-stock trading by members of Congress now attract serious bipartisan attention.

Most of this debate treats “Congress” as a single, homogeneous group. Our research suggests that’s the wrong place to look. When it comes to turning political information into stock market gains, a very small group of congressional leaders looks dramatically different from everyone else – in ways that matter for corporate governance, compliance, and investor protection.

Leaders don’t start out as star stock pickers – but they become them

We assemble transaction-level stock trading data for all members of Congress from the mid-1990s to 2021 and link those trades to firm outcomes. We then identify all lawmakers who ever served in formal leadership roles (Speaker, party floor leader, whip, or caucus chair) and match each to a “regular” member with similar tenure, party, chamber, age, and gender.

Two simple facts emerge:

- Before ascension, future leaders and their matched peers have very similar, and generally unimpressive, stock performance. On average, both groups underperform simple benchmarks. Whatever makes someone a future party leader, it is not superior stock-picking ability.

- After ascension, their paths diverge sharply. Once they become leaders, these same individuals begin to outperform their matched peers by nearly 50 percentage points per year on a buy-and-hold basis. The matched non-leaders do not experience comparable improvement.

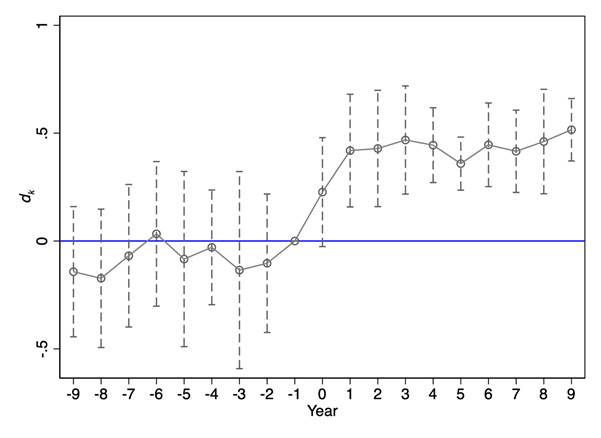

The figure below is a visualization of how leaders’ stock-picking performance changes in the years before and after they become congressional leaders. Year 0 is the year a lawmaker first enters a leadership position, and we set their performance in the previous year to zero for comparison. Each dot shows the estimated difference in one-year stock returns (relative to a factor-model benchmark) between leaders and their matched peers in a given year, and the vertical dashed lines show the statistical uncertainty (90% confidence intervals) around those estimates. We observe a dramatic increase following ascension to leadership.

Calendar-time portfolio tests, constructed to look like real-world investment strategies, tell the same story: alpha for leaders rises meaningfully after they gain leadership roles, while alpha for otherwise similar members remains flat.

The treatment group is small by design: only twenty lawmakers trade both before and after ascension over more than two decades. But these are precisely the individuals who control legislative calendars, influence oversight priorities, and attract the most intense corporate attention. That is where one would expect any political trading advantage to be concentrated.

Channel 1: Political information, influence, and the public sector side of corporate risk

For corporate boards, the first channel of concern is what we call political information and influence. Several patterns stand out:

- Majority control matters. Leaders’ trades are substantially more profitable when their own party controls the chamber they sit in. Whether their party controls the White House matters much less. The returns rise with control over the legislative agenda, not just party brand.

- Selling ahead of trouble. When leaders sell a stock, the firm is more likely to face regulatory or political trouble in the following months, such as investigations or hearings. The same individuals did not systematically anticipate these events before becoming leaders. That pattern is hard to reconcile with “good instincts” alone; it looks like trading on non-public political information.

- Procurement and public money. Firms whose shares are bought by leaders go on to receive more federal procurement business over the next one to two years, including a higher share of sole-source contracts. Firms leaders sell do not see a comparable drop. Given the sheer volume of contracts awarded each year, but the narrow set of firms leaders invest in, this looks less like passive foresight and more like selective advantage.

- Legislative voting and portfolio alignment. After leaders buy a stock, their party is more likely to vote in favor of bills that benefit that firm and to oppose bills that would harm it. Effectively, party-level legislative behavior becomes more aligned with the financial interests implied by the leader’s recent purchases. The evidence is weaker on the sell side: leaders and their parties seem more inclined to help firms they own than to hurt firms they have exited.

For companies, these patterns cut both ways. They suggest that:

- Public-sector risk is not only about being surprised by new legislation or enforcement, but also about how political influence may channel public resources toward some firms and away from others.

- When firms become the focus of interest from powerful lawmakers, the overlap between political risk and political opportunity becomes especially sharp. That has implications for how boards oversee lobbying, government relations, and procurement strategy.

Channel 2: Corporate access, selective disclosure, and insider-trading risk

The second mechanism is a corporate access channel. Corporate insiders have strong incentives to cultivate relationships with influential lawmakers, especially those who can shape regulation or committee agendas. But sharing material non-public information with a politician who also trades the stock creates classic insider-trading and fiduciary risk.

Our findings suggest that:

- Connections pay. After members become leaders, their abnormal returns are particularly strong when they trade in firms that have contributed to their campaigns or are headquartered in their home states – relationships where regular contact and information exchange are most likely.

- Trades anticipate executive-driven news. Leaders’ purchases are followed by more positive corporate news (such as dividend increases), while their sales are followed by more negative news. Critically, the predictive power is concentrated in events that company executives themselves would typically know well in advance. Leaders do not systematically anticipate external shocks such as lawsuits or competitor setbacks.

To a board or general counsel, this should ring familiar alarm bells. The patterns look much more like selective sharing of inside information with powerful officeholders than like better use of public disclosures. That raises questions not only about political ethics, but also about corporate compliance with securities laws and internal insider-trading policies.

What this means for boards, executives, and investors

What should corporate leaders and governance professionals take away from this? First, political relationships and trading risk belong in the same conversation. Boards often treat lobbying, PAC contributions, and engagement with policymakers as distinct from insider-trading and selective-disclosure risk. Our evidence suggests they are tightly linked at the very top of the political hierarchy.

Second, investors and stewardship teams may want to pay closer attention to firms that repeatedly appear in powerful lawmakers’ personal portfolios and in federal procurement data. The alignment of legislative support, contract flows, and corporate events with personal trades suggests that political connections can be a hidden driver of both upside and downside risk.

Finally, for policymakers and regulators, the main takeaway is not that “all of Congress is corrupt,” but that the intersection of concentrated political power and personal investing creates governance problems that current rules struggle to manage. Disclosure-based regimes like the STOCK Act have not eliminated the trading advantages of leaders. Stronger structural solutions – such as banning individual-stock ownership for sitting members or imposing much tighter, independently monitored restrictions on trading by leaders – deserve serious consideration.

For corporate America, the message is equally clear: when dealing with the most powerful lawmakers, political risk and insider-risk are two sides of the same coin, and both require board-level attention.

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.