The Expansion of ESG Beyond Proxy Voting

Case Study: Emissions Reductions Proposals

In this context, it is not particularly surprising that voting support for shareholder proposals has declined. Take greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction target proposals, for example. Following the SEC change, the number of proposals on the topic spiked, from 4 in proxy season 2021 to 29 in 2023, while average voting support has gone down each year.

Historically, these proposals had called for companies to develop their own targets and focused on issues like Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, which are under management control with more widely-accepted risks to shareholder value for companies in relevant industries. That approach appears to have contributed to shaping market practice: last year, 94% of S&P 500 companies disclosed Scope 1 and 2 emissions, and 85% had established targets to reduce them.

But with many such ESG practices now firmly established across the market, the proposals going to a vote increasingly cover topics where there is far less market consensus regarding the link to shareholder value, like downstream Scope 3 emissions that are beyond management’s control; or call for companies that have already taken steps to go even further, for example, by replacing relative emissions reduction targets with new absolute targets. In some cases, these proposals prescribe specific goals or outcomes, which many asset managers believe should be left to management and the board.

It’s not just the proposal requests that have changed, but where they are being submitted. Several years ago, emissions proposals were targeted almost exclusively at companies in heavily-emitting industries, such as oil and gas or utilities. More recently, they have appeared at companies that are less directly emissions-intensive, such as financial institutions. Overall, less than half of last year’s emissions proposals (41%) were submitted at companies where the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) viewed GHG emissions as a material risk.

In effect, the multi-year decline in voting support for emissions and other ESG shareholder proposals isn’t telling us about asset managers’ views on ESG – it’s telling us about their assessment of these proposals’ merits. Moreover, it’s telling us that the institutions choosing to incorporate environmental and social considerations are likely approaching their proxy voting decisions from a rational, economic perspective — and that many of their ESG concerns are already being addressed.

It’s the Economics, Stupid

There is a persistent misconception that support for any ESG-related issue must be ideological in nature. To the contrary, asset managers generally make voting, engagement and stewardship decisions based on their assessment of how the issues involved impact the bottom line over the long term. The same general approach, grounded in financial materiality and allowing for consideration of each company’s unique circumstances, including performance, size, maturity, risk exposure, governance structure and responsiveness to shareholders, underlies Glass Lewis’ benchmark voting recommendations. This benchmark policy is designed to reflect the current, predominant views of local-market institutional investors on corporate governance best practices, via a bottom-up approach that involves extensive discussions with a wide range of market participants, including institutional asset management and pension fund clients, public companies, public company organizations, academics, and subject matter experts, among others.

In those discussions, we’ve heard countless different (and legitimate) opinions about whether specific topics are relevant to shareholder value and how they should be addressed. Although most institutions with multi-decade investment horizons are likely to argue that flooding and wildfires could have a financial impact on an insurance underwriter, or that the presence of slave labor in a popular retailer’s supply chain could damage its brand, many opt to base their votes on a more traditional set of governance considerations, eschewing environmental and social factors — an approach that Glass Lewis actively facilitates through its Corporate Governance Focused thematic voting policy, one of the many tailored options our clients can employ as-is or as a base to build out their own custom policy.

Even among the many asset managers that do incorporate the long-term financial implications of ostensibly ‘non-financial’ issues in their assessment, the decision to support a given proposal covering those issues typically reflects a value-focused, case-by-case analysis of what, exactly, the proposal is requesting in the context of the company’s specific circumstances. That one disagrees with their assessment does not invalidate it.

The Role of Proxy Advisors

Another persistent misconception evident in the Journal’s narrative relates to the role, and purported ‘agenda’, of proxy advisors.

To be fair, the Journal is partially correct in stating that “fund executives are second-guessing” proxy advisors. They certainly are — but this is not a new development. Rather, it is how asset managers routinely use proxy advisor recommendations: as one of many inputs in forming their own vote decisions. Faced with tens of thousands of votes across their portfolios each year, proxy advisor research allows institutional investors to cut down on document review and identify the proposals that warrant in-depth, in-house analysis.

Further, the Journal’s suggestion that asset managers have ever merely “follow[ed] the direction” of proxy advisors is plainly false. There is extensive research showing that asset manager votes tend to align with proxy advisor recommendations on routine, non-contentious proposals, overwhelmingly those supported by management. On ESG shareholder proposals, asset manager votes varied widely, demonstrating that they make their own assessments, and ultimately their own voting decisions. Indeed, the supermajority of Glass Lewis institutional investor clients vote according to a custom policy or via a custom process for reaching vote decisions. And, whether they elect to receive vote recommendations according to a custom policy, a hybrid policy, or the Glass Lewis benchmark policy, our clients control how their actual votes are cast.

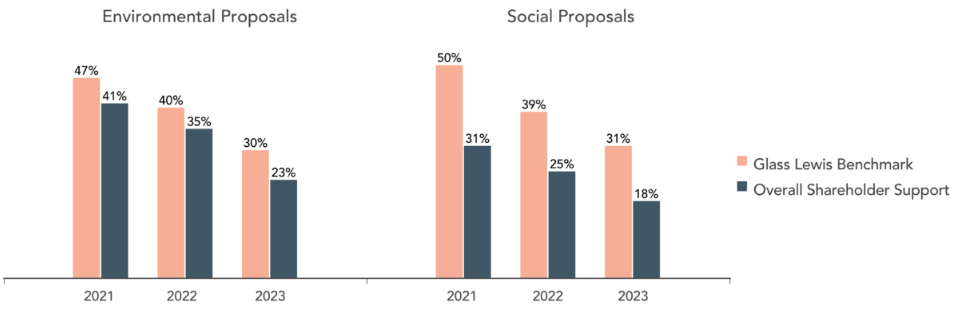

Similarly, the data flatly contradicts the Journal’s claim that asset managers have become more skeptical of proxy advisors. Over the past three years, the ratio between Glass Lewis benchmark policy recommendations on environmental and social shareholder proposals and the voting support those proposals received has remained consistent. In fact, the largest divide was in 2021, counter to the Journal’s narrative.

Glass Lewis is a business, not an advocacy organization. Our role as proxy advisor is not to persuade clients to adopt a particular voting policy or to vote in any particular way, but to provide corporate governance expertise, objective research and complementary tools to help them vote as they see fit. Our clients have a wide range of views, and we offer a wide range of corporate governance and stewardship solutions tailored to meet their needs. If we were pushing an agenda, encouraging clients to vote against their interests, or otherwise failing to assist them, we would not still be in business. That’s how business works.

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.