Discover Another Side of Southern Italy: The Life of a Village and Its People

SANTA FE, NM, UNITED STATES, January 6, 2020 /EINPresswire.com/ -- The Pentro — a special horse breed that has grazed in the same marshland for over 2,500 years—is one of the blessings that brought fame to a small Italian mountain village known as Mundunur. A recent title from Via Media Publishing illuminates the interrelationship between the village and the Pentro while providing the fascinating story of life in Mundunur from its origins to today.

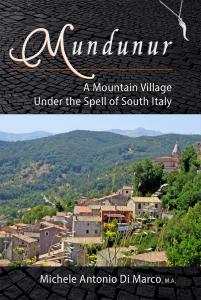

Just printed, the title of this book is Mundunur: A Mountain Village Under the Spell of South Italy. The subtitle is important since the village has been intimately tied to southern Italian culture and the ebb and flow of political power emanating from Naples. “Mundunur” is the local dialect referring to the Montenero Val Cocchiara, which roughly translates as Black Mountain with a Spoon-shaped Valley. It is located just over eighty miles north of Naples in Molise, the second smallest region in Italy, the youngest region, and the least known. The through coverage this book provides make it the turn-to reference for the village and for understanding the many other villages of south Italy.

Years of research supplied the author with an abundance of information. As a result, a wealth of cultural and societal details enrich the narrative that take the reader through each page. The first chapter is a delightful recount of the author’s early life in an Italian-American family, surrounded by immigrants who had origins in Mundunur. The character of these people and the stories they shared about the old country inspired the author to make his first trip to the ancestral village. His path takes the reader on an expedition of discovery. “What did my ancestors do in the village for work? What was their daily life like from morning ’til night over the seasons? What would they think of Montenero today?”

The following chapter tells of multiple visits to the village, meeting relatives, and gaining familiarity with the lives of the inhabitants. Although the first two chapters are captivating in themselves, they only serve to entice the reader to want to learn more about Montenero itself. The author first surveys the land, its geological formation from slow-moving tectonic plates and resulting array of spectacular mountain scenes. This is a logical start since the land’s character and climate is was determines what plants and animals are present.

We can now visualize the majestic landscape, teaming with abundant wildlife and highlighted with a seasonal display of colors provided by the trees and flowers. But when did humans actually settle in this pristine setting? We find the first paleolithic settlement in Italy only twenty miles from the village. Later, the land was under the Samnites and Romans, and eventually fascinating records show how the village was founded on the lands of the Abbey of San Vincenzo al Volturno just over one thousand years ago. Since then, invasions from the north and south played heavily on Mundunur, although the daily labors of the village peasantry remained unchanged. Official censuses made in 1447, 1753, and 1865 provide fascinating details about the medieval village and the lives of dukes and serfs living there.

Fractured by social-political pressures from foreign powers and internal rebellions, the southern regions eventually came under the forced unification of Italy at the end of the nineteenth century. While Mundunur inhabitants and other southerners were living at a bare subsistence level, they also soon came to face two world wars. In addition, major earthquakes and epidemics took a toll on the village. Political changes lead to rebellions and arrests in Mundunur and throughout the south. One of the solutions strongly supported by the government to existing problems was emigration.

For centuries, people made their living in the village by agriculture and raising animals. Modernization has dissolved that way of life. What does the future hold for Molise and the numerous mountain villages like Mundunur? Many are now being abandoned. If Mundunur is to survive and prosper, the key may be tied to the Pentro horse and the natural beauty of the landscape—attractions for a growing tourist industry.

Molise has been one of the most neglected Italian regions and relatively little information covers its history and culture. Some even say “Molise, It Doesn’t Exist.” This book welcomes all into the region through the roads of Mundunur. It fills a void in local historiography for the Molise region and offers insights on the history and evolution of hundreds of small villages throughout the south.

Find more details about the book at the Via Media Publishing website or on Amazon.com.

Michael DeMarco

Via Media Publishing

+1 505-470-7842

email us here

Visit us on social media:

Facebook

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.