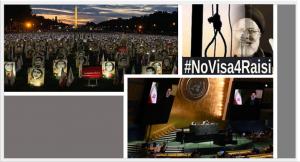

(Video) Iran: The Iranian people Urge the US not to Grant Visa to Raisi

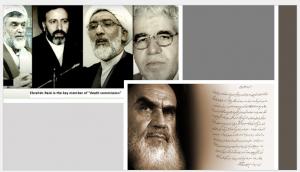

When Ebrahim Raisi, the Iranian regime’s current president, was a deputy prosecutor for the capital city in 1988, he became one of four officials tapped to serve on Tehran’s “death commission” and thus implement the supreme leader’s fatwa.

Nationwide, Iran’s 1988 massacre claimed over 30,000 lives, with about 90 percent of the victims being members or supporters of the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran. Although similar bodies had been assembled throughout the country.

Ali Khamenei had already appointed Raisi first as head of the religious foundation known as Astan-e Quds Razavi, then as head of the regime’s judiciary. These roles allowed him to the crackdown on a nationwide uprising in Nov. 2019, he killed 1,500 people.

Raisi took office, with some of the latest incidents being plainly directed toward the same goals as guided his actions at the time of the 1988 massacre.

For approximately three months that year, Raisi helped to interrogate political detainees at Evin and Gohardasht Prisons, whereupon the death commission ordered the immediate hanging of anyone deemed guilty of “enmity against God.”

Nationwide, Iran’s 1988 massacre claimed over 30,000 lives, with about 90 percent of the victims being members or supporters of the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran. Although similar bodies had been assembled throughout the country, the Tehran death commission was undoubtedly responsible for the largest single portion of those killings.

Furthermore, the regime’s then-supreme leader, Ruhollah Khomeini, personally gave a broader mandate to Raisi himself before the massacre was over in recognition of his uniquely enthusiastic implementation of the blanket death sentence.

That promotion was the beginning of a pattern that led right up to Raisi’s appointment as president. Khomeini’s successor, Ali Khamenei, publicly endorsed Raisi in advance of the June 2021 sham election and clear the way for him to stroll into the office.

Previously, Khamenei had already appointed Raisi first as head of the so-called religious foundation known as Astan-e Quds Razavi, then as head of the regime’s judiciary.

These roles allowed him to oversee, respectively, the financing of terrorism and extremist ideology, and the violent crackdown on a nationwide uprising in November 2019, which killed 1,500 people.

Raisi’s appointment was intended as a green light for further crackdowns, in the face of strong public defiance of the culture of repression surrounding the mass killings in 2019. Since then, the regime has undergone several more uprisings, each of them associated to some degree with the organizing efforts and expanding public profile of MEK “Resistance Units”.

So far, the people’s defiance has persisted, but the culture of repression has clearly intensified. Since Raisi’s appointment, the rate of executions in Iran has nearly doubled, with more than 600 being carried out so far in 2022, compared to a little over 300 in all of 2021.

This trend coincides with an accelerating rate of politically-motivated arrests, as well as a growth in the general enforcement of repressive laws, including those barring the practice of minority religions and mandating that women wear hijabs and separate themselves from men in society.

All of this underscores Raisi’s well-recognized identity as an unscrupulous criminal. For the international community, this, in turn, should raise alarms about the impact of that brutality on the prevalence of terrorist threats that are traceable to the Iranian regime.

Indeed, those threats have proliferated since Raisi took office, with some of the latest incidents being plainly directed toward the same goals as guided his actions at the time of the 1988 massacre.

In July, the Iranian Resistance canceled a planned international conference at the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran (PMOI / MEK) compound in Albania, known as Ashraf 3, after it became clear that credible threats had been made against the gathering.

The existence of those threats was revealed at roughly the same time as Albanian authorities reported they had been investigating suspected Iranian operatives in the country for four years, ever since another terrorist plot against Ashraf 3 was thwarted.

That 2018 incident was not the only one of its kind, nor was it the most. In June of the same year, an Iranian diplomat-terrorist named Assadollah Assadi smuggled a bomb into Europe and conveyed it to two fellow operatives allow with instructions for detonating it at the crowded event near Paris organized by the National Council of Resistance of Iran.

Alongside tens of thousands of Iranian expatriates from throughout the world, that event was attended by dozens of American and European lawmakers, scholars, and other dignitaries.

After that plot was thwarted by law enforcement, Assadi was eventually put on trial in Belgium and sentenced to 20 years in prison. Shockingly, though, he may already be on the cusp of release, barely four years into that sentence, based on a treaty between Belgium and Iran that allows for the “transfer of sentenced persons” to serve out their sentences in their home country.

Even more shockingly, the treaty explicitly allows Iran to vacate the sentence Belgium handed down against Assadi or anyone else who is lawfully detained for any serious crime.

The treaty is seemingly intending to secure the release of a Belgian aid worker who has been taken hostage by the Iranian regime, but it nonetheless reflects a tendency toward woefully inadequate policies for dealing with Iranian terrorist threats.

That inadequacy is made all the worse in light of the fact that Assadi’s actions preceded a sharp hardline turn by the clerical regime one that plainly reflects an even greater preoccupation with attacking or otherwise undermining the greatest threat to the mullahs’ hold on power, which is also the leading voice for Iranian democracy.

The lamentable lack of assertiveness behind the pending prisoner swap is not unique to Belgium or even the European Union.

It is also reflected in the fact that the United Nations has left open an invitation for Raisi to attend the 77th session of the General Assembly in September, while the United States has made no move to prevent Raisi from visiting New York.

This is unacceptable on both counts because it conveys disinterest in the face of mounting terrorist threats while also turning a blind eye to Raisi’s implication in multiple severe crimes against humanity.

Perpetrators of the 1988 massacre have yet to be tried accordingly. However, steps have been taken in that direction in recent years. In 2019, a former Iranian prison official named Hamid Noury was arrested after arriving for a visit to Sweden.

He was indicted for war crimes on the basis of participating in the 1988 massacre at the end of the eight-year Iran-Iraq War. Noury was finally sentenced to life in prison in July.

The following month, survivors of the 1988 massacre and relatives of its victims filed a lawsuit against Ebrahim Raisi in the US federal court system.

The suit was accepted by the Southern District of New York, and although it remains to be seen whether it will go to trial, it already stands as a rare and vital acknowledgment of Raisi’s history.

The US treasury has already designated Ebrahim Raisi for his role in the violation of human rights and due to his background should not grant him a visa to visit New York for the UN General Assembly. Granting him a visa sends the opposite message to Tehran, and that would potentially reinforce Tehran’s preexisting sense of impunity at a time when Raisi’s presidency makes that even more dangerous to the world.

Shahin Gobadi

NCRI

+33 6 61 65 32 31

email us here

Raisi butcher of 1988 Massacre in Iran Ebrahim Raisi, A return to darker days or a declaration of character by the theocratic regime?

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.