DOCTOR DOLITTLE & WORLD WAR I by Colleen Adair Fleidner

If Hugh Lofting hadn’t been a soldier in World War 1, would he have written those delightful novels about a kind-hearted man he named Doctor Dolittle?

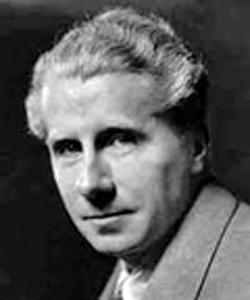

Who was author Hugh Lofting, and how did he come up with his unique story ideas? His early years weren’t particularly extraordinary. In fact, for a boy born in 1886 England, his childhood was seemingly ordinary. On the other hand, his interest in animals and nature emerged at an early age. Collecting leaves and flowers and bugs he’d found when roaming outdoors, young Hugh reportedly smuggled them into his bedroom, creating a tiny zoo and nature center which he hid in his wardrobe closet.

The child of Catholic parents, Hugh Lofting attended the Jesuit boarding school at Mount St. Mary’s in Sheffield, England. His desire for travel and adventure became apparent when he decided to go to college at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the United States. This was his first trip to America, and although he returned to England to finish his degree, his time in the U.S. had made a lasting impression.

Most surprising is that even though he loved to write, Lofting chose to study civil engineering, a more practical and profitable vocation. After graduation, he worked as a civil engineer in such faraway lands as West Africa and Cuba. But in 1912 he returned to America and settled in New York City with his new bride, Flora Small. That’s when he finally launched his career as a writer, producing articles for various magazines. This was his life’s dream. Two children, Mary and Colin, were born, and everything was going well. That is, until 1914 when a war broke out in Europe.

During the early years of the war, Lofting worked for the British Ministry of Information in New York. But as time passed and reports of tens of thousands of soldiers’ deaths filled the newspapers, Hugh Lofting, who had remained a citizen of Great Britain, made the life-changing decision to serve in what was called “The Great War.”

It was 1917. Lofting was 31, older than many of the soldiers who had been called to serve in the war. Returning to England, Lofting signed up to join the Irish Guards, a distinguished group of Irish soldiers who fought alongside the English regiments despite the two countries’ past differences.

Despite the graphic newspaper accounts of the horrors of the war, few people were prepared for the reality of it: Living in the ghastly trenches that zigzagged along the Western Front in France with hundreds of corpses littering the region known as “No Man’s Land,” the now-barren fields between the German and Allied troops. Dead and dying animals – horses and mules for the most part – added to the repugnant scene that stretched for miles. Living with the ongoing anxiety that another gas attack or that a bomb might land in the trench at any moment created what we now call “PTSD.”

For Hugh Lofting, the war was unbearable. He fought alongside his compatriots, but at night when he was supposed to rest, he wrote. At first, he struggled to put pen to paper, reluctant to send letters home to his wife and children. What could he say? Should he tell them about this, the most terrible thing he had ever experienced? The only thing that would accomplish was to bring his loved one’s fear and worry.

Worst of all, there was no end in sight. He watched his friends die. Limbs were blown off. Germans with flame throwers burned men alive right before his eyes. And the animals…the poor innocent creatures had no choice in this abominable conflict created by human greed. Little could be done for the dogs, horses or mules who had to obey their masters. Each time he saw one of the animals lying in the field dying, he wanted to help. But what could he do? Climbing out of the trenches to attempt to care for them likely meant being shot by a German.

Hugh Lofting had to find a way to mentally block out what was his reality. He was a dreamer; an artist at heart who had no stomach for these killing fields. Instead of letting the disturbing images of the war fill his mind, he dreamed up a kindly veterinarian, Doctor Dolittle, a rotund little man who loved nature and all its creatures. Dolittle was so in tune with his animal patients, he could communicate with them in their own language. Even sea snails warranted the good doctor’s attention.

Lofting created an imaginary world that was filled with adventures and fun, with warmth and humor to entertain his children. His stories were told in letters complete with pen-and-ink drawings, many of which later showed up in the Doctor Dolittle books would be published in the 1920s. Thankfully, he survived a serious injury when he was struck by a piece of shrapnel from a hand grenade. He was sent back to England to convalesce and eventually returned to his family in New York.

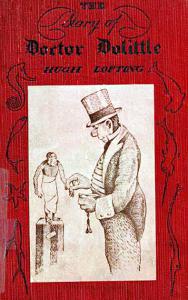

Flora Lofting had found Hugh’s letters so beautiful and Doctor Dolittle so endearing, she kept them until his return, begging her husband to expand the stories and write them as books. Moving his family to a farm in Connecticut away from the hustle bustle of New York City in 1919, Hugh Lofting wrote his first book, “The Story of Doctor Dolittle: Being the History of His Peculiar Life at Home and Astonishing Adventures in Foreign Parts. Never Before Published.”

It was an instant hit and, although Lofting said he didn’t necessarily write the book for children, it was classified as a children’s classic. He wrote another and then another each year between 1922 and 1928, winning honors and prizes in the process.

Sadly, his wife and greatest fan, Flora, died in 1927. He married Katherine Peters in 1928, but she, too, passed away before they celebrated their first anniversary. Not surprising is that Lofting suffered through the next years in a deep depression. Not until five years had passed did Lofting release another Dolittle book, “Doctor Dolittle’s Return.”

He married Josephine Fricker in 1935 and the next year, after his son, Christopher, was born, he moved his family to sunny California, to a beautiful home in Topanga Canyon. He finally wrote another book, “Doctor Dolittle and the Secret Lake,” a 12-year-long labor of love for his toddler son, Christopher.

When World War 2 broke out, the man who had become a pacifist after experiencing the Great War, the man who always had loved and honored animals, sat down and wrote a gut-wrenching poem sharing his feelings about the futility and horrors of war, entitled “Victory for the Slain,” published in Britain in 1942. After a lengthy illness, Hugh Lofting died at a hospital in Santa Monica, California in 1947 at the age of 61.

“What is war?” I asked.

“Oh, it’s a messy, stupid business,” he said. “Two sides wave flags and beat drums and shoot one another dead. It always begins this way, making speeches, talking about rights, and all that sort of thing.”

“But what is it for? What do they get out of it?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “To tell you the truth, I don’t think they know themselves.”

from Doctor Dolittle and the Green Canary by Hugh Lofting

Tory Hartmann

Sand Hill Review Press

+1 415-297-3571

email us here

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.